Stable industries require a well-defined, largely predictive approach to managing projects. Less stable environments, by contrast, require a more adaptive approach – to both strategy and project management.

This post explores an old rule in strategy for stable industries, the Rule of Three and Four. It looks at the impact it has, when it applies today, and alternative, more adaptive approaches to PM and strategy in situations where the rule does not apply.

The Rule of Three and Four Explained

In his article “The Rule of Three and Four“, published by Bruce Henderson, founder of Boston Consulting Group (BCG), in 1976, Mr. Henderson stated it simply:

In his article “The Rule of Three and Four“, published by Bruce Henderson, founder of Boston Consulting Group (BCG), in 1976, Mr. Henderson stated it simply:

“A stable competitive market never has more than three significant competitors, the largest of which has no more than four times the market share of the smallest.”

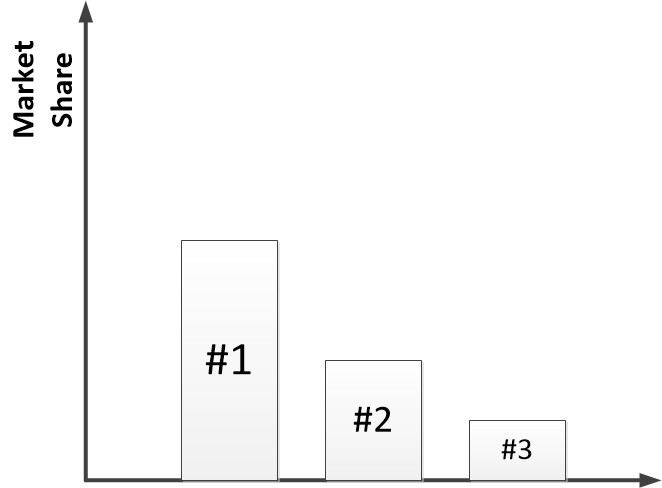

He observed that as businesses developed through the various stages of business growth, once an industry matured, a common market share hierarchy evolved. The leader’s market share was roughly twice that of competitor #2, whose market share in turn was roughly twice that of competitor #3. That means that the market share of competitor #1 was roughly 4x that of competitor #3. Finally, he stated that any additional competitors with less market share could not be viable.

Henderson noted:

“The Rule of Three and Four is a hypothesis. It is not subject to rigorous proof. It does seem to match well observable facts in fields as diverse as steam turbines, automobiles, baby food, soft drinks and airplanes. If even approximately true, the implications are important.”

Hence, we have a theory, rooted in general observation at the time, that showed a pattern in the competitive environment. The basis for the thinking was that cost was a function of market share – and volume – based on the experience curve. BCG did later perform extensive research that supported the observations.

Does the Rule of Three and Four Apply today?

The rule seems to apply today, but decidedly in larger, more stable industries.

The rule seems to apply today, but decidedly in larger, more stable industries.

First, many stable industries have roughly three dominant competitors, and the market shares of each do seem to roughly follow the pattern of have 2x the market share of the next fourth.

But how many industries are ‘stable’, and how can you tell?

The general guideline is to determine if industry market shares have fallen into the Rule of 3 and 4 pattern:

- Does the leader have a share of roughly 50%, the second a share of about 25%, and the third roughly 12-13%?

- And of those that are stable, based on recent experience, how long might they remain stable?

- If the industry is still developing, does it look like it will eventually evolve into this pattern?

If stability is measured by frequency of strategic planning cycles and the use of agile vs waterfall project management methods, then today there is less stability. Shorter duration industry life cycles – like competing in arenas instead of broader industries – would seem to be the evolving pattern.

The past era of stable industry leaders included industries such as steel, chemicals, and automobiles. Industry leaders at the time included such names as United States Steel, Union Carbide, and General Motors. Today, that has been largely upended, and the new leaders are companies such as Facebook, Apple, Tesla, and Google. These companies are large and have commanding market shares.

Do they, or will they, follow the Rule of Three and Four?

The rule clearly does not apply everywhere. Where it does not apply – where the industry is not ‘stable’ – competitors need an ‘adaptive’ approach. Indeed, even for an industry that is stable, that stability could eventually be disrupted, or become destabilized. In addition, many industries may never actually reach such a stable state, as they may disappear before then.

Strategic implications to the Rule of Three and Four

If the industry is stable and fits a Three and Four configuration, companies need to focus efforts on maintaining their share. If a competitor falls below the top three, the business is likely not viable, and they should seek to exit either by being acquired, repositioning assets, or considering some other consolidation endgame.

If the industry does not fit a Three and Four configuration, but appears to be headed in that direction, building a leading market share is a priority. There will be questions about just what strategy to follow, as there are risks to being too aggressive and not aggressive enough, as seen in studies of the experience curve.

When an industry is not stable and does not appear to be heading that way based on the product life cycle, the following ideas can help navigate to an appropriate ‘adaptive’ approach that applies:

- Strategy Framework Canvas – sort through different considerations to find the right strategic framework

- Strategic Agility – conceptualize an approach to being adaptive

- Economies of Scope – identify possible synergies among different parts of the business

- Ansoff Matrix Model – visualize strategic options: market penetration/development, product development, or diversification

- Dynamic Capabilities – build a core adaptive competency within the organization

- Blue Ocean Approach – find uncontested marketplaces, and even build a leadership position

- Lean Innovation – discover and build a business around the hotpots for customers and markets

- Design Thinking – follow a rigorous process to precisely deliver what customers want, not what demographics show

These are some more common adaptive strategy approaches to use in situations where the Rule of Three and Four does not apply.

Project Management and the Rule of Three and Four

In industry, it is important to be aware of the overall competitive environment. Here are some questions about the industry related to the Rule of Three and Four to consider:

- Is it stable, requiring predictable performance on projects?

- Is it growing toward stability, requiring a hybrid adaptive and predictable approach?

- Is it highly unstable and unpredictable, requiring a mostly adaptive approach?

—————————————-

I recommend these PM templates (paid link):

—————————————-

Here are the impacts to planning and executing projects, depending on the answers to those answers.

Planning projects

- When planning projects, the selection of a target objective is a function of where the overall organizational strategy falls on the scale of predictable to adaptive.

- In a predictive environment, with stable underpinnings and where the Rule of Three and Four applies, target objectives will usually be very clear. Cost, schedule, and quality will be well understood. Well-defined projects will be the norm.

- In an adaptive environment, where market instability and change are present, and where the Rule of Three and Four does not apply, target objectives can be murky. Smaller projects, often with the objective of learning, can be very helpful in moving things forward.

Executing projects

- When executing projects, the metrics are a function of where the overall organizational strategy falls on the scale of predictable to adaptive.

- In a predictive environment, with stable underpinnings and where the Rule of Three and Four applies, metrics related to the target objectives will usually be very clear. Cost, schedule, and quality will be relatively fixed. Project success will be measured on achieving these clear metrics.

- In an adaptive environment, where market instability and change are present, and where the Rule of Three and Four does not apply, target objectives can be murky. Smaller projects, often with the objective of learning can be very helpful in moving things forward.

Predictable vs adaptive does not necessarily mean projects should be managed with waterfall vs agile approaches. For example, a software project in a predictable stable environment of a market leading company will still probably be done using agile methods as part of a hybrid approach.

Resources

The following is the original Rule of Three and Four article by Bruce Henderson, and a “revisit” article from about 10 years ago, both published by BCG:

“The Rule of Three and Four“, by Bruce Henderson, Boston Consluting Group (BCG), 1976.

“BCG Classics Revisited: The Rule of Three and Four“, by Martin Reeves, Michael Deimler, George Stalk, and Filippo Scognamiglio, Dec 2012

The following are related resources (these are paid links):