While that book covers both the static and dynamic side of strategy, this post focuses on the dynamic side, or strategy dynamics.

What is Strategy Statics?

Here is how strategy statics line up along three parallel dimensions:

- Strategic thinking approach – The static side lines up with Michael Porter’s original industry structure, or Five forces approach, which takes industry structure as a given.

- Financial reports – The static side is a bit like a balance sheet – a snapshot in time.

- Project management methodology – The static side is like the waterfall method, which assumes that conditions will remain relatively constant, or static, over time.

The consistent thread for strategy statics is that it refers to the existing. It does not consider the market size, what action to take to achieve competitive advantage, and the critical nature of timing in taking those actions.

Strategy statics is skewed to stability; it does not consider the fact that markets grow and shrink. It does not cover what strategic advantages might be achieved and how. It also does not cover timing issues – such as the phases of development of a market, company, or industry.

See my post on power and strategy for a more focused view of strategy statics.

What is Strategy Dynamics?

Here is how strategy dynamics lines up along the same three parallel dimensions as above:

- Strategic thinking approach – The dynamic side, at its extreme, lines up better with digital startups, which find their way through undefined territory until they ‘figure it out’, their market does not initially exist, it later matures, and an industry structure emerges.

- Financial reports – The dynamic side is somewhat like an income statement, which is a scorecard for performance over a particular period.

- Project management methodology – The dynamic side is more akin to the agile method, which assumes constant change, plans and executes over short durations, and adjust plans frequently based on results achieved and feedback received.

The consistent characteristic in strategy dynamics is that the general thrust is toward ‘invention’ or some type. That means that something currently does not exist, or has not been established.

What is this ‘something’ that is being invented? Hamilton Helmer outlines that it could be a product, a process, a business model, or a brand.

The important thing is that not only does it require focused action, but the timing must be right. I am going to especially focus on the timing, as it will have the most effect on project managers – those who implement strategic initiatives.

Why is timing is so important?

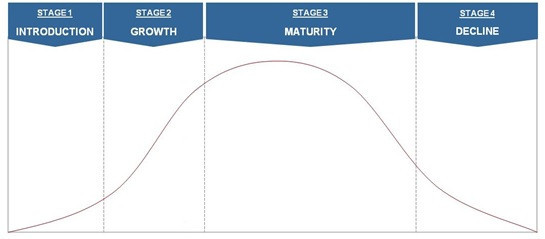

It’s because the building of moats – the natural protections around a business that allow it to protect its competitive edge – is time critical and tied to the product life cycle stages – Introduction, Growth, Maturity, and Decline – and other market maturity cycles.

Here is a look at the 7 powers that characterize these moats, and how timing is critical in terms of the product life cycle stages:

- Scale economies – A business can only build scale during the Growth stage; it’s too early in the Introduction, and too late in Maturity and Decline.

- Network economies – Similar to building scale, a business can only build scale during the Growth stage.

- Counter-positioning – This occurs typically in the Maturity stage – at least in that stage for the ‘incumbent’, or current market leader. Counter-positioning is the disruptive force that upends the incumbent’s leadership position and sends it into Decline.

- Switching costs – There is not cost of switching in the Introduction phase, and it gradually builds during the Growth stage and is in full bloom in Maturity. By the Decline phase, market forces are such that it does not matter much anymore.

- Branding – Branding begins to take hold in the Growth stage, but does not fully take grip until the Maturity phase. It is losing its power during the Decline phase.

- Cornered resource – Obtaining the services of a unique high-value resource most often occurs in the Introduction phase. This is what prevents competitors from gaining an advantage. I would argue, however, that cornered resources of different types can happen at the other stages, too, as long as the resource is especially expert and adept at getting results during that phase – such as an ability to shepherd growth, to manage resources especially well during Maturity or Decline.

- Process power – Process advantages cannot occur until there is sufficient volume, which usually does not occur until well into the Growth stage, and definitely during the Maturity phase.

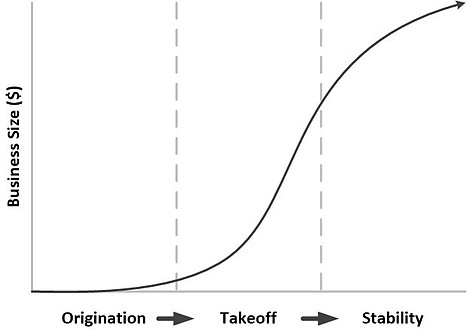

Hamilton Helmer takes an alternate approach – Power Progression – to that of the product life cycle, but I think it has similarities and may be good enough in most situations. One major difference is that the Power Progression includes an Origination phase which does not even occur in the Product Life Cycle, as it precedes the Introduction phase.

His approach is captured in the following graphic.

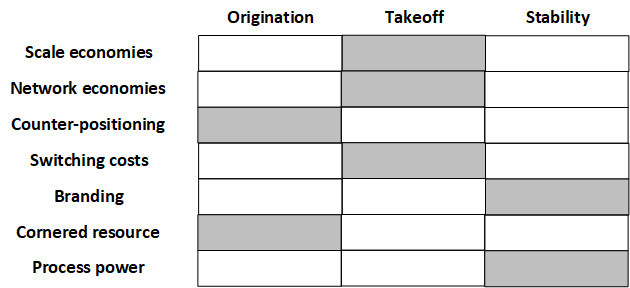

In this alternative graph to the product life cycle, the 7 powers map to the Power Progression Stages, in terms of when they need to occur – for similar reasoning to that of the product life cycle mapping above – as follows:

The above shows that timing is critical, and projects that are devised to build moats and competitive advantage are only of value when timed properly.

When is each important?

While Hamilton Helmer argues that both sides – static and dynamic – are critically important and essentially joined at the hip, I wonder if that applies mainly in the startup world, where companies and industries are being created.

Alternatively, I think that the static side applies as a nice, easy-to-use framework for companies in established industries – stable and not high growth companies. It can provide a framework for them to identify areas where they can analyze their current position and even build a competitive advantage by applying fresh strategic thinking.

Furthermore, I think that the dynamic side can apply to such established companies where they may develop a digital side of the business. That could be, for example, something that borrows on the strengths of the existing business and digitizes some aspect and creates a whole new industry dynamic.

How does Strategy Dynamics effect my projects?

—————————————-

I recommend these PM templates (paid link):

—————————————-

Strategy dynamics has the biggest application in project portfolio management – selecting the right projects at the right time. It also has a place in the implementation of projects, where metrics including timing come into play.

Project portfolio management needs to be tightly in sync with strategy. When a company is building moats – competitive advantages which make competitors both unwilling and unable to challenge – it must clearly to be in touch with the temporal considerations as outlined above.

Some questions that a project portfolio manager might ask include, “When can a particular project that contributes to building one of the 7 powers have the most effect?”, “When do you need to start planning such a project?”, and “By when does it need to be executed?”

When managing or implementing a project, it matters a lot how it maps to the 7 powers. Your work in implementing project starts right where the portfolio manager’s work finished.

Here are some questions that you, as a project manager and implementer, should ask: “What metrics do I need to make sure we are on track toward the objective?”, and “How will we know the project was successful?”

The timing is not necessarily fixed and may be more tied to observing feedback and identifying inflection points than to a specific timeline.

How do I apply Strategy Dynamics in practice?

I have focused in this post on the timing of projects, which is a big part of strategy dynamics. That’s where I think project managers can become more acutely aware – of the effect of the temporal nature of strategy related to their projects.

Much of strategy dynamics is about timing of strategic actions. I think project managers need to first internalize strategy concepts – such as the 7 forces – in order to have a command of these powerful market phenomena. With a good command, use your strategic thinking to clearly articulate what your project needs to achieve and when. Then devise metrics not only for project execution progress, but also for progression toward contributing to the company’s position in the market.

To learn more about strategy dynamics and the ideas discussed in this post, I strongly recommend you read “7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy” by Hamilton Helmer.

—————————————-

I recommend these strategy resources (paid link):

—————————————-